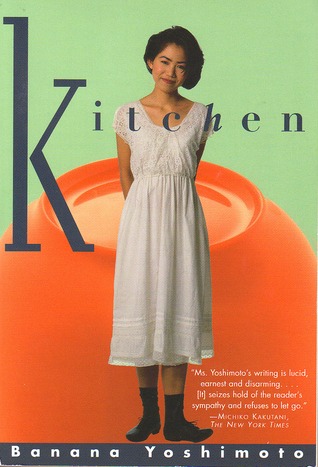

Kitchen

Reviewed May 1, 2017 on The Litt Review.

I’ve been reading Mishima since I was too young to know better; this has been followed up by Oe, Kawabata, Dazai, and, like everyone else, Murakami. Recently, however, I realized that I had only been reading Japanese male authors. So, I put a call out on Twitter, asking for suggestions for female writing from post-war Japan. Kitchen by Banana Yoshimoto kept being recommended.

It’s a darling book. The version I got also includes Moonlight Shadow, a short story with a similar theme - love and loss. The two stories give a good approximation of Yoshimoto’s writing, which otherwise I wouldn’t have a focal point on (with only one data point). In short, she writes these emotional, broken little passages that have a clear, simple beauty to them. Passages like:

I loved his hearty robustness, I thirsted after it, but in spite of that I couldn’t keep pace with it, and it made me hate myself. In the old days.

Or:

I was aware of all that, but the beauty of her tears was something I would not soon forget. She made me realize that the human heart is something very precious. Under the blue sky, inhaling the clear, sharp bite of winter air, I was overwhelmed by it all. What should I do? I had no idea. The sky was blue, blue. The bare trees were sharply silhouetted, and a cold wind was seeping through. “I can’t believe in the gods.”

Or:

“What’s this?” he said, laughing, and – although it wasn’t the most creative gift – took it from my palm and wrapped it carefully in his handkerchief as if it were something precious. He surprised me: it was not typical behavior for a boy that age.

They’re wonderful, and littered through the book. But instead of coming off as ominously serious, you are able to stay on the surface; enjoy them as they come, without ending up in a pit of saccharine despair. She also writes with some humor, here and there:

“Really.” Yuichi smiled. “Maybe we should go into business. Our clients could pay us to move in with people they want dead. We’ll call ourselves _de_struction workers.”

And,

I shrugged off my pack. Lying there on my back, I looked up at the roof of the inn and, staring at the glowing moon and clouds, I thought, really, we’re all in the same position. (It occurred to me that I had often thought that in similar situations, in moments of utter desperation. I would like to be known as an action philosopher.)

The writing is marvelous. The stories themselves - about a girl who loses her parents, and moves in with a transgender mother and her son, and her connection to them, or about a girl who loses her love to a car accident at the age of twenty, and finds solace in an inexplicable Brigadoon-esque Japanese myth - are moving, and interesting, and somehow very Japanese. They reminded me of Murakami. Kitchen was published in 1988, and we haven’t progressed much in magical realism since then. It feels like it could be written today.

What’s different about Yoshimoto from other, male authors is the emotional depth to the stories, and the viewpoints. All of the sudden, I’m reading about a girl who has an urge to share the best soup with her lover, and so takes a taxi fifty miles to give it to him. It doesn’t feel ridiculous, at all. But it wouldn’t fit at all in any of Mishima’s work, with their almost perverse introversion. Of course, you could a gender bias coming from the first line - “The place I like best in this world is the kitchen” - and few of Mishima’s main characters are female, so this change is expected. But it is very well done.

Finally, the translation was great - but unfortunate. It’s very hard to translate from Japanese, with different registers for female and male speakers, into English. I wondered if

When my grandmother died the other day, I was taken by surprise.

was a translator error - it sounds so nonchalant. And later, when the transgender mother writes in a letter:

Just this once I wanted to write using men’s language, and I’ve really tried. But it’s funny - I get embarrassed and the pen won’t go. I guess I thought that even though I’ve lived all these years as a woman, somewhere inside me was my male self, that I’ve been playing a role all these years. But I find that I’m body and soul a woman. A mother in name and in fact. I have to laugh.

I wish I could have read this in the original, to get it fully. As it was, it was hard for me to tell the difference between the female and male hand. There was one bit that was close:

“Yuichi,” I said, “the fact that you’re relaxed enough with me now to tell me how you’re really feeling is a source of comfort to me. It makes me very happy. So happy I feel like shouting it from the rooftops.” “What kind of talk is that? Sounds like it was translated from English.””

The first paragraph sounds intensely like a bad American sitcom, which I think is what the translator was getting at.

I’ll have to brush up on my Japanese to read it again.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.