The Dark Tower

Reviewed Jul 9, 2017 on The Litt Review.

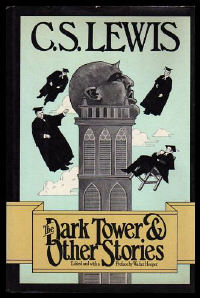

Browsing through an Edinburgh bookshop to kill time, I noticed a huge section of CS Lewis books. This wasn’t surprising - what was was the copy of The Dark Tower I saw there. Previously, I thought this was only a book by Stephen King, and I would have bet £20 that CS Lewis hadn’t written such a book. Opening it, I found out it was an extension, from unfinished manuscripts, of Lewis’s space trilogy, which I’ve read many times since I first discovered them when I was around 13, and which I love. I had bought an extra copy of Voyage to Venus (called Perelandra in the States) a few weeks earlier, because the cover was so awful. There were a few other short stories he had finished or written to an extent they were worth publishing, thrown in for free. I bought the thing immediately.

The Dark Tower itself is only around 85 pages long, and is set after That Hideous Strength, mostly in Cambridge. Some men devise a way of looking into the future through a screen. The future is dark - a man sits in a room with a huge stinger coming out of his forehead, and seems to sting random supplicants who walk into the room, to turn them into automatons. Through an accident with a light switch, someone ends up going through into the other world, and eventually grows a stinger himself. Around then, the entire plot ends. It makes less sense when you read it all the way through.

A few things are curious about the story. For one, Lewis goes on about how modern women talk about anything, and don’t seem interested in romantic notions. The story completely fails the Bechdel test, but that’s nothing new for Lewis.

Another thing is that it is, strangely, utterly perverse.

He - or it - began to perform a series of acts and gestures so obscene that, even after the experiences we had already had, I could hardly believe my eyes. If you had seen a mentally deficient street-urchin doing the same things at the back of a warehouse in Liverpool docks, with a grin on his face, you would have shuddered. But the peculiar horror of the Stingingman was that he did them with perfect gravity and ritual solemnity and all the time he looked, or seemed to look, unblinkingly at us.

And, later, when Scudamour (our man who falls through the screen into the future world) grows a sting:

But what startled him far more was that in the very act of setting the girl down he found his whole mind reeling under the effort of resisting a desire which horrified him both by its content and by its almost maniacal strength. He wanted to sting. There was a cloud of pain in his head so that he felt his head would burst if he did not sting. And for one horrible moment it seemed to him that to sting Camilla would be the most natural thing in the world. For what other purpose was she there? Of course Scudamour has read his psychoanalysis. He is perfectly well aware that under abnormal conditions a much more natural desire might disguise itself in this grotesque form. But he is pretty sure that this was not what was happening. The pain and pressure in his forehead, as he still remembers them, leave no room for doubt. This was a desire with a real physiological basis. He was full of poison and ached to discharge it. As soon as he realized what his body was urging him to do he fell back several paces from the chair. He dared not look at the girl for a few minutes, whatever assistance she might need: certainly he must not go near her.

According to a commentary on the section, Lewis never realized this was in any way sexual. I find that hard to believe. It reminds me incredibly of FLCL, an influential and fantastic short Anime series where a young man has a horn grow from his forehead - the entire series serves as a metaphor for adolescence. Lewis, it seems, never went through adolescence at all. I laughed at several points in the book at the naïvety of the writing.

The book also makes fast and loose with time travel theories. That’s fine - ultimately, it has to be fiction - but by making his characters fail to point out gaps in the internal logic, he makes them look somewhat silly. For instance, there’s a ruling out of time travel in general because there’s no way for atoms to be in two places at once - how could an atom in this time be in another time, when it is being used in the other time? This isn’t a problem, assuming that the atom goes back to the original timeline. He also mentions the issue with putting molecules into a space where other things are - not that big of an issue, considering you can have a body dropped into a vacuum without an issue. Like all time travelers, he completely ignores the movement of planets through space all the time, such that looking at the same place in another time is actually impossible, because we’re already hundreds of miles from where we were when you started reading, as the sun is rapidly expanding outward with the rest of the galaxy (not to mention the planet moving around the sun).

His take on linguistics was also, frankly, humorous.

Before I go any further I had better explain that as long as he lived in Othertime Scudamour found no difficulty in speaking and understanding a language which was certainly not English, but that he did not succeed in bringing a single word of this language back with him. Orfieu and MacPhee both regard this as confirming the theory that what occurred between him and his double was a real exchange of bodies. When Scudamour’s consciousness entered the Othertime world it acquired no new knowledge in the strict sense of the word ‘knowledge’, but it found itself furnished with a pair of ears and a tongue and vocal chords that had been trained for years in receiving and making the sounds of the Othertime language, and a brain which was in the habit of associating those sounds with certain ideas. He thus simply found himself using a language which, in another sense, he did not ‘know’. This view of the matter is borne out by the fact that if, in Othertime, he ever attempted to think what he was going to say, or even paused to choose a word, he at once became speechless. And if he failed to understand what an Othertimer said to him he could never lay his finger on any one word and ask what it meant. Their utterances had to be taken as a whole. When all went well, and when he was thinking hard of the subject-matter and not at all of the language, he could understand; but he could not take their talk to pieces linguistically or pick out nouns and verbs or anything of that sort.

Language doesn’t work this way. Ears don’t - your brain does not overtrain on your own language to the point where it can understand vocalizations immediately. And the oratory organs don’t, either, although there might be something said about vowel space and your likelihood of moving your tongue in certain places statistically more often than others, depending on your mother language.

Overall, though, I was fairly amused, so I’m still glad I read it.

The other stories were of varying quality. One, of a man regaining his sight later in life, has now been done by science - we have people now who are able to see who never were, before. It would be interesting to compare their perspectives. Unlike the protagonist in Lewis’s story, I don’t think that newly-sighted people are likely to completely be confused by what ‘light’ is, and to jump into a cloudy bank of fog off a cliff because they want to catch it.

Another story blatantly suggested that women are more interested in hats than anything else, so we’re not going to talk about it.

There were two rather good stories. One, about a man who travels to the moon to discover why the other three missions there died soon after landing, is wonderful, and I don’t want to spoil it for you. It’s a quick read, and is called Forms of Things Unknown. It makes the entire book worth reading - go find it.

The other story, After Ten Years, was custom written with me as the intended audience, I think. It’s based in Troy, during the fall, from the perspective of Menelaus. He sacks Troy, and looks for his wife - Helen - and finds that she has grown old and is now no longer beautiful. This puts him in a quandary - why did they fight for ten years? At the end of the story, he’s in Egypt, with his wife again, when someone points out that the Helen he has with him is, in fact, not Helen, but an eidolon - the actual Helen has been with Paris this whole time, in Egypt, living the good life. This is an old concept - Homer certainly toyed with it, as did Euripides. But Lewis’s writing is fantastic and wonderful. I wish he wrote more of the story.

Do you want to get book reviews and notes from books I read in your inbox? Sign up! I'll include a summary, my favorite quotes from the book, and any vocabulary I found interesting or didn't know already.